Process: Roughs for Megaton Man #14

The Original Golden Age Megaton Man Meets the Uncategorizable X+Thems #1

After the debacle over renumbering Megaton Man #11 and completing The Return of Megaton Man #3 under duress—which I never could have accomplished at all if I hadn’t already plotted and thumbnailed the entire story arc beforehand—I was really in no mood to consider more projects for Kitchen Sink Press at all.

Apparently, I had spoken with the publisher over the phone around the time Return #3 was going to press about future plans, and their takeaway was that I was stuck on ideas. Not really. I had finished what I started and, as I had predicted in my letter of November 18, 1987—not threatened, mind you—the renumbering had shattered my sense of creating an ongoing, lifelong work; it had dampened my enthusiasm for the character and IP; and I had to think twice about allowing my imagination down the Megaton Man path any further. I was thinking twice.

The publisher’s takeaway from that phone conversation was that I was merely stuck on ideas. They promptly provided a list of suggestions for possible Megaton Man one-shot #1s—including superhero parody ground I had already covered—which was entirely at odds with the advice of my editor, Dave Schreiner, to push in a more character-driven direction that relied less on parody or, in his words, “boff[ing] on the biz.”

In other words, my publisher’s advice was diametrically opposed to that of my editor—they suggested I lean into nothing but parody and “sting[ing] some deserving targets.”

This included the now-infamous suggestion of a Dolph Lundgren Punisher movie parody.

At least I intend to repeat it so many times that it becomes infamous, and deservedly so.

This pallid plea seems so pathetic in its naivete now I could almost cry. I mean, this wasn’t a young fan suggesting, “Gee, I think it would be cool if the Six-Million Dollar Man visited The Planet of the Apes,” but an esteemed art-house publisher who had recently accused me of selling out.

I did have more ideas for Megaton Man—although, as you’ve caught on by now, I’d have much preferred them appearing in consecutively-numbered issues of an ongoing series rather than mini-series or one-shots. The Return of Megaton Man, predictably, sold modestly—the first issue, with a #1 on the cover, perhaps a few hundred more than the other two.

For all the sturm und drang over renumbering, a black-and-white Megaton Man from #11—not unlike Scott McCloud’s Zot! #11 on after the first ten color issues—would have worked better in the long run for building a readership and establishing a brand.

But, if one-shot #1s were all I was to be allowed for my now broken, shattered brand, I would give it a try. To quote Megaton Man: “As long as it’s temporary!”

The fourteenth Megaton Man comic book would be called The Original Golden Age Megaton Man #1 and would feature the character of Uncle Farley, who had been revived in The Return of Megaton Man. If I was going to do one-shots, at least they would highlight my own cast, not parody versions of Marvel or DC trademarks, as my publisher so fecklessly suggested.

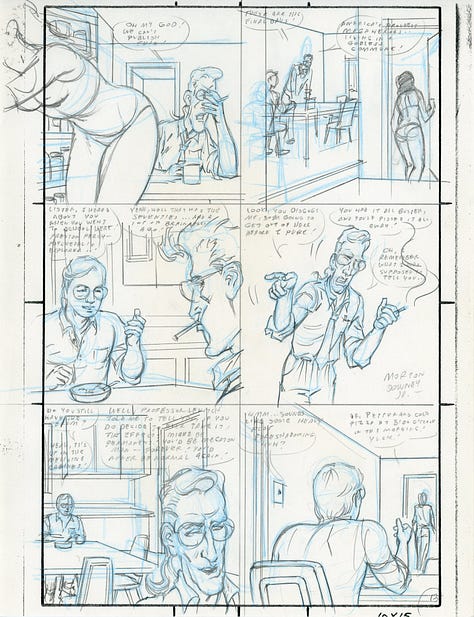

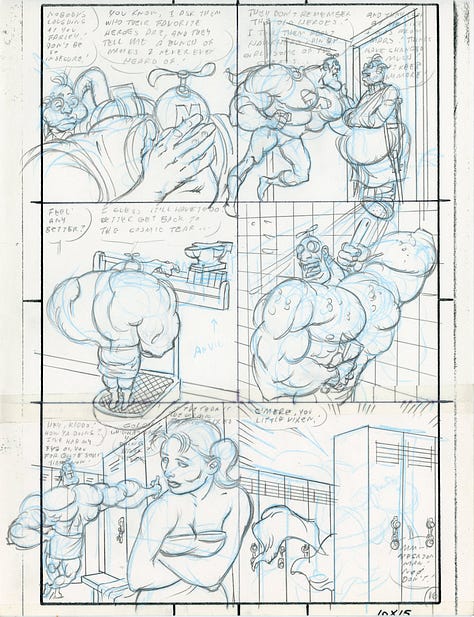

I proceeded to thumbnail and script the book in a larger and tighter format that could be light tabled (traced) onto the Bristol board for lettering and inking. This was a further development in my process, derived from experience freelancing.

However, before the work was completed, I renamed it The Original Golden Age Megaton Man Meets the Uncategorizable X+Thems #1 and devised a logo that traded off the obvious parody. I’m sure I came to this decision myself without prodding from the publisher, internalizing at least to some extent their craven outlook that the Megaton Man IP was completely worthless unless it adopted such a blatantly parasitic marketing gimmick.

It is this aspect that I am most ashamed of and that still angers me the most. But I had already had my head beaten in over numbering and even my choice of inker—so as any trauma survivor will tell you, ya better get internalizin’ if ya don’t want another whuppin’.

Although the storyline involves Uncle Farley, along with Rex Rigid, presiding over a team of Youthful Permutations, it has nothing to do with any storyline Chris Claremont ever conceived—simply because I never read X-Men.

In fact, the X+Thems are so generic—and that’s the point—that only four nameless characters stand out. Later, I would give them names and call them the Y+Thems (“Why them and not me?”), and they would factor into The Ms. Megaton Man Maxi-Series a great deal.

There are a few surprisingly personal touches in the issue, which was expanded to 32 pages from the previous 24, such as a “normal” Megaton Man dream sequence and Clarissa James becoming Ms. Megaton Man. Still, it deserved to be a longer, multi-issue story arc.

The publisher insisted the title be shortened to Megaton Man Meets the Uncategorizable X+Thems #1, which, strictly speaking, wasn’t even true; Trent Phloog doesn’t really become Megaton Man, nor does he really meet the X+Thems. It was the Original Golden Age Megaton Man who was meeting the Uncategorizable X+Thems.

But it also wasn’t the first issue of anything—it was the fourteenth. If you see my point. The elimination of “The Original Golden Age” from the title: Another symbolic—shambolic—victory for Kitchen Sink Press!

Although the thumbnails indicate the interior pages as numbered 1 through 33, I demoted page 1 to the inside front cover, making it pages 0 through 32 in the published comic book.

What is interesting about my process at this point is that I was now using 8.5” x 11” grids to rough out my page layouts. Previously, I had used grids that were a quarter or a half that size—a process I had begun probably during Border Worlds and developed further in my freelance work for DC and Mirage. For example, I had thumbnailed Megaton Man #11 in quarter-sized thumbs, but then redrew them “by eyeball” onto the 11” x 17” Bristol board.

With the layouts for X+Thems, since they were larger (the grid is merely a sloppy blow- up of the smaller, quarter-sized version), I could draw more tightly, then enlarge on a photocopier and light table (trace rather than redraw by eye) onto the Bristol board. Sometimes, tracing in this manner results in a certain stiffness, but I thought the control gained was worth the trade-off. I would continue to vary and experiment with this process into the 1990s.

One final note: This issue, when shot by the printer, always seemed a little light; the art had been slightly overexposed in the camera room and some finer details had been lost. At the time, I asked production manager Jim Kitchen to have a page reshot to confirm this—I still have the results, although we never went back to press. I look forward to seeing this corrected in The Complete Megaton Man Universe, Volume I: The 1980s, which I scanned and remastered myself, coming later in 2025.