In January of 1987, I sent in a plot synopsis for Megaton Man #11 to my publisher, Kitchen Sink Press. Shortly thereafter, my editor, the late Dave Schreiner, replied enthusiastically, seemingly cheering on the character-driven direction I had chosen—one that, incidentally, tended to minimize the superhero parody aspects of the previous ten issues.

Correspondence of the time suggests the publisher never even bothered to read this synopsis or even skim the later thumbnails I produced later in the year. As I began actually drawing the issue, they insisted on renumbering Megaton Man #11 with a new #1. When I expressed my displeasure at what I perceived was reneging on their commitment to publish Megaton Man #11, they excoriated me with a barrage of withering verbal abuse.

Somehow, I finished the story arc I had outlined.

After I completed The Return of Megaton Man #3—what I had intended to be Megaton Man #13—the publisher wrote to me again, suggesting that I fragment and diminish the Megaton Man series even further into a series of Groundhog Day #1 one-shots that allowed room for little or no narrative advancement of the core cast of characters I had grown quite fond of.

Apparently, we must have spoken on the phone, and I had expressed little interest in creating anymore comics for them at all, which they interpreted as being stuck on ideas. But I had ideas for Megaton Man—just none that they regarded as having any value, or of any importance to me.

They offered several suggestions that seemed like nothing more than rehashing of ground I had already covered before—if you can rehash old ground—and nothing that seemed worth devoting more than a few panels or pages to at most. And yet the idea was to feature the spoof prominently in the logo and on the cover, which would have demanded milking these lame ideas to the point that they would eat up a sizeable chunk of the book—lest fans should feel cheated.

And I wouldn’t want to be accused of cheating the fans after the publisher had accused me of cheating the fans, now, would I?

Most memorably, they suggested I spoof the forthcoming Dolph Lundgren Punisher movie—which most likely would have already been long gone from theaters and completely forgotten before I could ever complete even a rush-job comic book.

My hunch is such a spoof comic would have bombed so bad it would have made Harold Hedd: Hitler’s Cocaine look like a perennial best-seller.

The problem with the #1 one-shot schema was two-fold: one, I already had a narrative in mind for the characters, a new milieu, and stories I wanted to pursue—a second wind and a firm, new foundation that could have sustained a decade of Megaton Man that I would have to set aside or minimize to the vanishing point, making the ordeal utterly unappealing to me; two, not only would I have to design a new logo every time out, emphasizing whatever trademark was being spoofed at the moment—let’s say The Pugilist for The Punisher—and reduce my creator-owned IP, Megaton Man, to supporting-role status.

Besides, how much of the comic book was I supposed to devoted to the spoof and how much to the story I actually wanted to tell? Fifty-fifty? Thirty-Seventy? Why include the Megaton Man IP at all?

And what if readers didn’t “get” that The Pugilist was supposed to be The Punisher? Complete fail.

Note: At the time, I never even tried to think up spoof names for The Punisher—I made up The Pugilist. Maybe The Puniator? The Pusilanimator? The Pushover? Sorry, but nothing’s grabbing me.

Moreover, renumbering every issue with a #1 and featuring whatever fad of the month seemed topical—wasn’t that more or less the schema for normalman?—may sound easy, but it added a layer of unwelcome complexity to the creative process. It was also diametrically the opposite advice from their own editor.

Why not just get another creative team altogether to do The Pun-Scheister—still a flat line—and leave prima donna Don Simpson and Megaton Man the fuck alone?

This was the same publisher who chastised me for being a sellout and a hack, and who was now expecting me to take made-to-order requests based on whatever fad seemed hot in the comic book market at the moment. For peanuts.

These were the values of a Victor Fox, not an esteemed art house publisher.

Yet, when Megaton Man was the hottest thing they’d ever published—in the summer of 1985, sold out issues #1 and #2 were going for $12 and $9 respectively—they adamantly refused to go back to press.

Maybe this is why I happen to think Kitchen Sink Press was run by a complete fuck-up.

Those who have chastised me recently as I have posted these reminscences seem to have as shallow an appreciation for Megaton Man as the publisher. They seem to think it should have been easy for me to conform my creative imagination to whatever marketing imperatives a publisher demanded—however mercurial, fleeting, and meretricious they might seem.

And the fact that I couldn’t—that must be proof that I was some insecure egotist, a jerk, a punk, a spoiled holdout …

If I were taking requests, wouldn’t I have been much better off just freelancing for Marvel or DC at significantly higher page rates? That was the career I half-heartedly backed into, by the way—so I could keep a roof over my head while still creating my creator-owned IP for Kitchen Sink Press—but in retrospect should have dived in wholeheartedly.

And never looked back.

Frankly, Kitchen Sink Press wasn’t paying me enough to tell me how to create Megaton Man—ostensibly, my creator-owned IP.

Or maybe it just has to be my idea.

There was a profound misunderstanding of how I created Megaton Man in the first place. It was never a parody of contemporary trends and fads. It was a send-up of things I had read and loved as a kid but had outgrown—and in some cases that were still being soullessly perpetuated by hired hands long after the originators were no longer in the picture.

I had used up most of my store of fond memories in the early issues of Megaton Man and was already running dry, and spoofing current fads—which would have required me to actually read that dreck—couldn’t have interested me less.

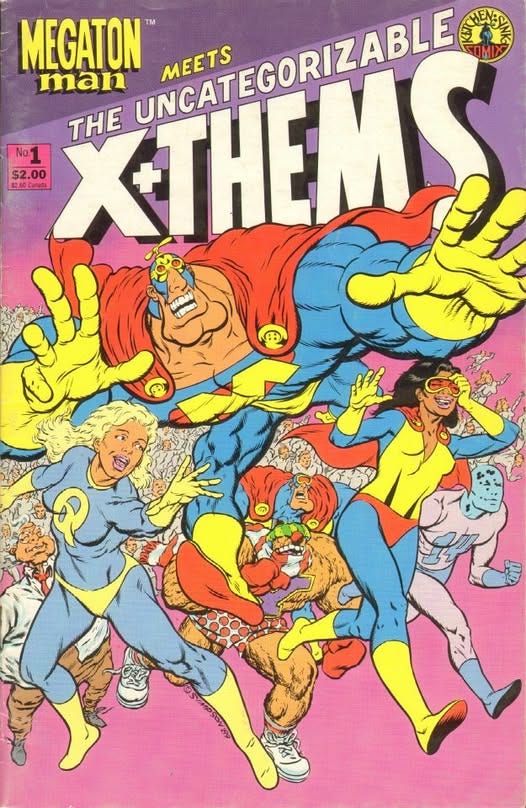

In any case, I tried it their way—but could only manage Megaton Man Meets the Uncategorizable X+Thems #1 (originally, The Original Golden Age Megaton Man #1), Yarn Man #1, and Pteranoman #1 (only one-third of a Megaton Man comic) before my imagination completely shut down.

I simply could not get enough throughput of the character-driven story I wanted to tell through this ill-advised schema of #1 one-shots. It was simply too fragmentary, too confusing, too contrived.

Critics siding with the publisher will say I was being passive-aggressive, doing number #1s but only featuring my own cast of characters, which contravened the whole ploy.

Yeah! Because what earthly good would it be for me to own The Pukisher after the Dolph Lundgren dud landed with a thud?

The extra trouble renumbering caused simply wasn’t worth it—just as I had predicted. Not only did it mean extra and unwelcome creative labor for me that slowed me down every time I wanted to return to my familiar characters; I also believe it diminished back-issue sales and created shelving problems for retailers, scattering Megaton Man back-issues throughout the alphabet, and losing fans.

It was a branding disaster.

In fact, I literally met fans at shows who hadn’t heard about Yarn Man #1 at all—it just got lost in the noise. And these were fans who were tuned into any new Megaton Man news.

I believe Megaton Man #11 would have sold as well or better to loyal fans and that a little encouragement instead of denigration would have prompted more and more frequent Megaton Man comics from me in the long run—I have a track record of trying to please.

Kitchen Sink Press was an impotent publisher who had failed at color comics and had completely run out of gas in the Direct Sales Market, and could only resort to meaningless, feckless, and consciously unethical gimmicks that, in the long-run, hastened the decline of sales of my comics, frustrated me at the drawing board, and diluted my brand.

But at every turn, it was always my fault, never theirs.

The damage to what could have been a sustainable and productive (and indefinite) new run of Megaton Man comics was squandered in needless acrimony, stupid obstacles thrown in my way by the publisher, and foolish short-sightedness.

Worst, it toxified any fondness I had for the character of Megaton Man for quite a long time.

It would take years for me to recover and regroup creatively and begin to feel like I was rebuilding and recovering the Megaton Man narrative I had intended—but only after I had parted ways from the imprint once and for all.

They even had the obtuseness to ask me to sit down and plan with them how together we might go about remedying the chaos they had created—after rejecting the character-driven plan Dave Schreiner and I were agreed upon.

I had a story I wanted to tell. My editor supported it. My publisher couldn’t have cared less about my “convoluted storylines”—all they wanted were first day sales that parasitically siphoned off of the competition and revenues they could plow back into money-losing pet projects or even more dubious get-rich-quick schemes.

Who was calling who a hack and a sellout?

And if the editor and publisher were split, shouldn’t the tie have gone to the cartoonist and supposed creator-owner of the IP? Such was the freedom of eighties independent comics, kids.

I wonder if they even conferred with one another. No wonder Dave remained behind in Wisconsin when the company moved to Massachusetts.

The never-ending torrent of lame one-off parody-covered number one issues would eventually be the strategy of Dave Sim in his post-artist phase, with nightmarishly-bad results. I quickly gave up on ordering them for our shop, but Overstreet gives each and every one of them its own listing (while jamming everyone of the dozen or so CRACKED magazine spin-off mags in the main mag’s listing, to cite just one counter example). For the record, your one-shots have always been filed with their parent title in our back-issue bins (with BIZARRE HEROES and BORDER WORLDS filed separately).