In the fall of 1985, I decided I would bring Megaton Man to an end with issue #12. The circumstances surrounding this decision are a bit difficult to reconstruct—I was living at Kitchen Sink Press at the time, which means that most communication was conducted face-to-face, unlike other times when letters and faxes have survived as historical documentation. But let me try to sketch it out for you.

Megaton Man #1 had originally been conceived as a one-shot. I created it over a 13-month period—roughly late winter 1983 through spring of 1984—while living in Detroit, where I worked odd jobs washing dishes in a restaurant and working at an office supply store near the GM Building. I submitted photocopies of the finished issue to some fifteen different publishers and magazines, most of which are now defunct (I was rejected by Gary Groth at Fantagraphics twice), but got a positive response from Denis Kitchen.

Denis wanted to know if I could do a series on a monthly or bimonthly basis—sure, what did I know? It had only taken thirteen months to do my first-ever comic book, and I had no inkling of how to do a series, a story arc, or even a coherent script. Denis, I am convinced, was willing to take a chance on a complete newcomer only because Megaton Man seemed like a plausible color comic for his fledgling Direct Sales Market post-underground line (which included The Spririt and later Death Rattle, both in costly color).*

The first issue of Megaton Man had ended with the love interests—Pamela Jointly and Stella Starlight—leaving Megatropolis and a bereft Megaton Man behind. Where the story went after that, I had no idea. In fact, the entire premise of that first issue was that Megaton Man had endured for 999 repetitious issues in which, at the conclusion of the adventure, everything returned to normal, only to start over again from square one.

But at the conclusion of issue #999, things did not return to normal; the gals, tired of the toxic boys’ club, split for a Route 66 road trip to see America, declaring “Right on, Sister!” In the following issue, Megaton Man would fill Stella’s role in the Megatropolis Quartet, but that would be be merely a stopgap before the team’s inevitable demise. Things were falling apart.

Writing and drawing a color comic book series at the age of 23 was an opportunity, don’t get me wrong. Somehow, I managed to eek out several more issues. But my decision to terminate the series with #12 in the fall of 1985 was predicated on two points: In the first place, Denis adamantly refused to reprint the first two issues (which had sold out almost immediately) since they were in color, and set-up costs for a shorter reprint run would have lost money†; secondly, because certain competitors had sent a “Cease and Desist” to us for my kidding around with their trademarks. The writing was on the wall.

I came to the conclusion that Megaton Man would never achieve more than cult status, so I launched a science fiction back-up feature, Border Worlds with issue #6 and began planning my exit strategy. Around issue #8, I drew the covers for #9, #10, #11, and #12, setting the final trajectory of the series. We even announced Megaton Man would conclude with issue #12 in the current Amazing Heroes preview issue.

By the spring of 1986, however, the color line of comics as a whole was hemmorhaging money, Megaton Man being the only profitable tent pole whose profits held up The Spirit and Death Rattle, both of which had declined in sales to a point they were losing money. Denis called us all into the office—me, editor Dave Schreiner, and art director Pete Poplaski—and announced the end of the Kitchen Sink Press color comics line.

I faced a choice of presenting the final two or three issues of Megaton Man in black and white or curtailing the series in color with issue #10. Since I hadn’t done more than covers for those respective issues, it was easy to compress the story material I had in mind into the space remaining.

I say that now, but I realize that most of the material that got cut were character-driven subplots involving the civilian secret identities of the characters; what remained were the crowd-pleasing superhero parody elements that presumably were more popular with fans (and the publisher). This is exemplified by one of the covers that was never used, featuring a forlorn Pamela Jointly staring into space, wondering what had gone wrong with her youthful aspirations:

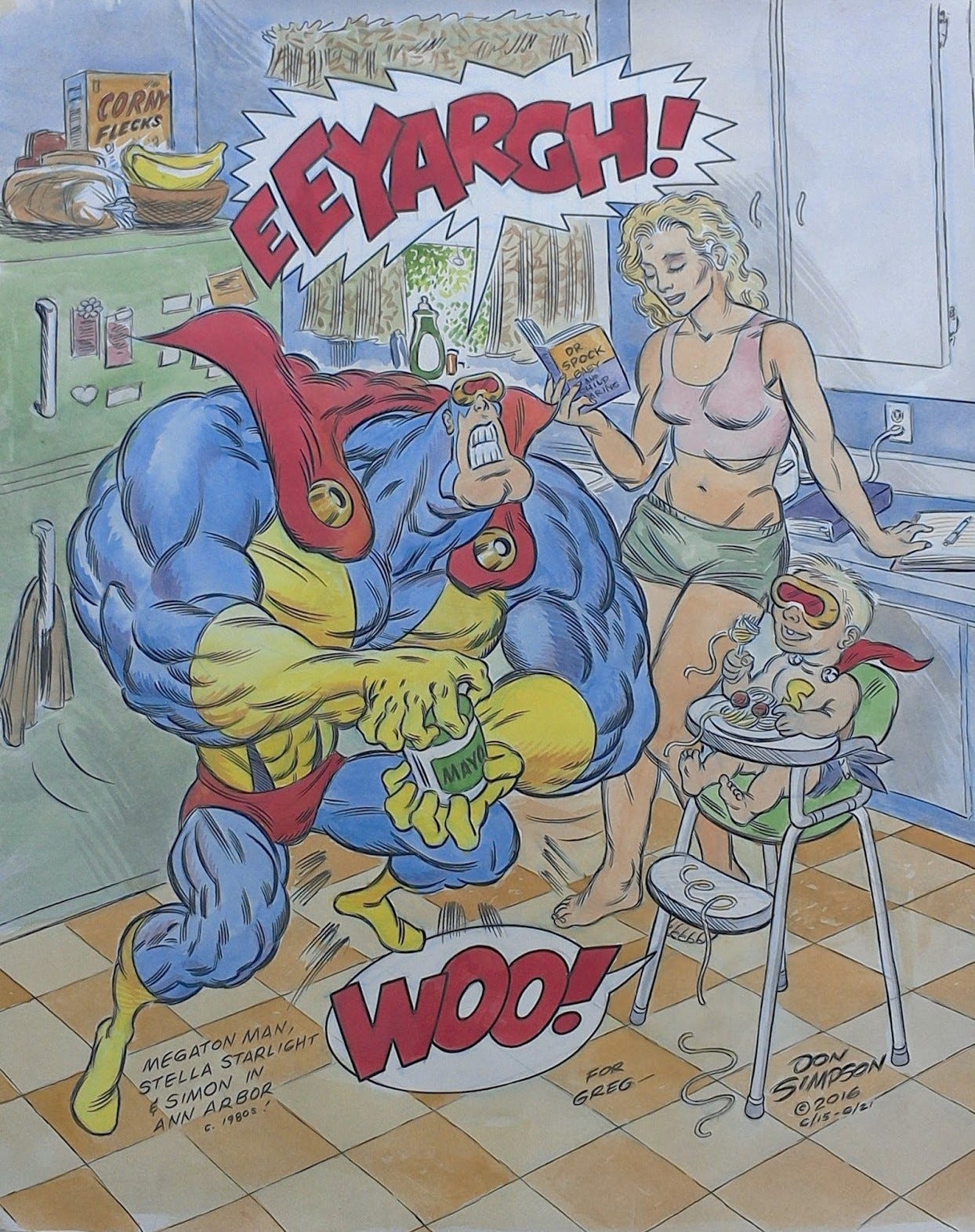

Jump ahead: After seven issues of Border Worlds, I returned to Megaton Man. The new storyline, following the loss of Megaton Man’s megapowers in issue #10, followed the characters to Ann Arbor, where they had all wound up. Pammy was now teaching journalism at her alma mater while Stella, pregnant with Megaton Man’s love child, had enrolled in classes to resume her college education. Trent Phloog, the de-powered Megaton Man, shows up in civilian guise with the hopes of playing a role in his child’s life, if not Stella’s affections.

This “Ann Arbor” storyline, as I’ve come to call it, was the basis of The Return of Megaton Man #1 through #3, which I had hoped to simply call Megaton Man #11-#13. By this time, I had actually learned to type out my plots instead of scribbling on the back of envelopes, and submitted it months in advance while still working on what would be the final issues of Border Worlds. My editor, Dave Schreiner, praised this character-driven approach that minimized the superhero parody and treated the characters not as spoofs of household-word trademarks but as worthy comic book characters in their own right.

The publisher, however, was less concerned with what he regarded as my “convoluted storylines” exploring the civilian identities and more concerned with gimmicky and ultimately futile new #1s and silly fight scenes—diametrically the opposite advice from that of his editor—which I discuss at length elsewhere.

The point is, tensions with the publisher being what they were, the character-driven civilian-identity subplot once again lost out to the superhero spoof in The Return of Megaton Man. The subsequent one-shots of the late 1980s (Megaton Man Meets the Uncategorizable X+Thems #1, Yarn Man #1, and Pteranoman #1) also gave short shrift to character development in favor of more repetitious, silly fight scenes—although these were not completely without at least a few melodramatic, soap opera moments.

In any case, it was an unsustainable formula for me, and I abandoned the publisher, as well as Megaton Man, altogether by the end of the decade. I discuss all of this at length in the forthcoming Complete Megaton Man Universe, Volume I: The 1980s (Fantagraphics Underground, August 2025). Suffice it to say, by the time I began Don Simpson’s Bizarre Heroes in the 1990s, Ann Arbor already seemed like passed-over backstory not worth doubling-back for and salvaging.

The irony is that the Ann Arbor setting was rich in story possibilities; I felt a creative second wind with Megaton Man—the character and the IP—after only a short sci-fi respite. The new locale, I felt, offered a solid foundation that potentially combined a Silver Age sensibility with a post-underground countercultural milieu—hippies, tenured radicals, Pentagon-funded experiments in campus labs, secret agents, UFOs, drop-in megaheroes and megavillians from Megatropolis—not to mention the inevitable if contrived moments in which Trent Phloog would regain his Megaton Man megapowers—as long as it was temporary.

This assertion is harder to prove since I made no notes at the time, and indeed did not permit my imagination to wander too far ahead of any given issue I was working on. But it stands to reason that Stella would be in school for a while; Simon, her son, would be a child for a while; and, given Stella’s determination to provide normalcy and stability for Simon’s childhood, Megaton Man seemed likely to remain ensconced in its midwest college town setting for a good chunk of time.

If I do say so myself, Megaton Man might have even evolved into the quintessential post-underground Kitchen Sink Press series—if the publisher had only supported a character-driven approach, rather a nine-hundred and ninety-nine issue rerun of the two sold-out issues it refused to reprint.

I should have been stronger. I should have insisted on the convoluted, character-driven (and presumably less commercial) storyline. But the votes of Dave and I did not equal the vote of Denis, and the Ann Arbor storyline got lost.

The best I can say is that I have managed to restore some of that lost vision in the prose Ms. Megaton Man Maxi-Series (a retelling of the Megaton Man mythos from the point of view of Clarissa James, Ms. Megaton Man) and in storylines still on my drawing board (namely, Megaton Man and the Doom Defiers). I’ve planted a few Easter eggs in X-Amount of Comics (Fantagraphics Underground, 2023) and a few more in the forthcoming Megaton Man: Multimensions (Cosmic Lion Productions, summer 2025).

Glimpses of the lost Ann Arbor storyline can be seen in the extant eighties comics and in the current work-in-progress in flashback, which is less satisfying than if I had explored those ideas more robustly at the time. Who knows, perhaps I lacked the life experience and maturity to tackle the material I had in mind anyway. Perhaps in many respects it will be better, richer now. I do know that it still haunts me, and it’s why I’m still doing Megaton Man forty years later.

This time, I’m not backing down. Stay tuned.

*In retrospect, Megaton Man may have been the closest thing to a perfect Direct Sales Market commodity the company would ever offer, if only because it had capes and muscles. It would certainly go on to become the hottest comic it published in 1985, or perhaps ever.

†I argue that even had second printings of Megaton Man #1 and #2 lost money, it would have increased readership of successive issue, building a readership and achieving a more sustainable income for me and for the company in the long run (incremental reprintings of sold-out issues is how Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Bone, both black-and-white titles, had built up larger and larger readerships). Denis argued perversely that a sold-out collector’s item would spark more interest in the title, which was counter-intuitive to my way of thinking. It seemed to me, therefore, that Megaton Man would forever be trapped in a cult-status and my best best was to try a different series altogether; hence, Border Worlds. Needless to say, it didn’t work, although it was more than a worthwhile experiment, and regenerative to take a break from Megaton Man.

Don, why not just compile it all in a Jim Rugg-style process zine? Megaton Man: Uncommercially Ann Arbor? I bet a bunch of folks, like me, would be interested.