Jim Rugg recently composed a publication of “found” ads, reviews, and promotional materials from the comic book year of 1986—he declines to autograph this work of “promo porn,” which I think is a mistake—it’s as fine a work of scholarship as any produced in comics academia, and he’s the author of it.

I recently wrote about 1986 myself, twice, almost by coincidence, as the year I felt the first of many “sea changes” in comics—less than two years into my career.

Now, let’s get to 1987.

In the spirit of Jim’s treatise, I’m taking found objects (in this case, documents from my extant archive) and created a visual archive here. The main difference being that these are primary sources—actual correspondence, selectively presented. But let’s assume my PhD has some meaning and I’m employing scholarly rigor—I’m not leaving out exculpatory evidence, at least not intentionally.

Now, a lot happened in 1987—the founding of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, which my publisher was instrumental in; the optioning of Megaton Man by screenwriter Stephen DeSouza (Die Hard) that was never renewed and obviously never turned into a live-action motion picture, which again my publisher was instrumental in; there was also the fallout of the black-and-white bust, taking my space opera Border Worlds with it; and last but not least, what I can only assume was a painful divorce between my publisher and his wife of seven years, one of only four full-time employees at Kitchen Sink Press.

I’ve beaten this dead horse before and elsewhere, so I’m going to present these documents with minimal editorializing for context.

Note: Fuller documentation may exist in the Kitchen Sink Press Records, 1965-2013, at Columbia University. I have not visited the archive in person myself. Letters and notes I may have mailed into the publisher along with original art, etc., may not be among my extant files but present there, and phone conversations, obviously, were never documented. I invite scholars to visit Columbia for themselves and am interested in any documentation that refutes my assertions here and elsewhere.

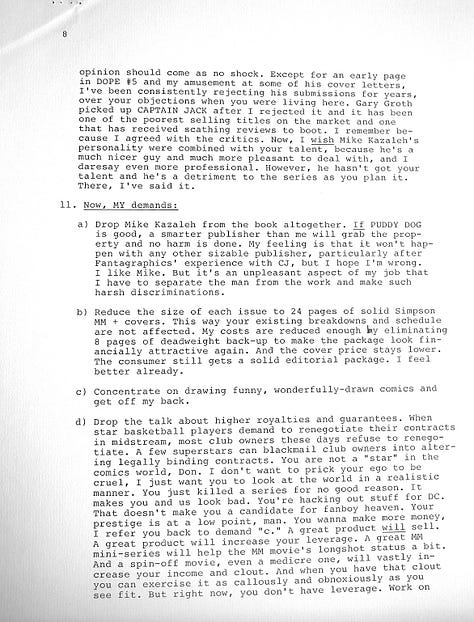

The above letter from December 16, 1986 sets the tone quite well. My publisher reports that the big companies are stomping on the little guys (as I suggested in a previous post), and things are starting to get ugly. This document makes a perfect prelude to another dated January 26, 1987, already reproduced in a previous blog, reporting that “Armageddon is here.”

Context: At the time, I had just moved from Van Nuys, California, in Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley to the north, where I only stayed about five months, back east to Pittsburgh. I was still at work on Border Worlds, issue #4 in fact (there would be seven in all, not counting Marooned #1, which appeared much later), although sales were already in free-fall.

In the new year, it would reach a point where I would have soon become homeless were it not for Mike Gold, who would offer me work on DC Comics’ Wasteland, scripted by John Ostrander and Del Close, with nine-page stories and covers drawn by four rotating artists.

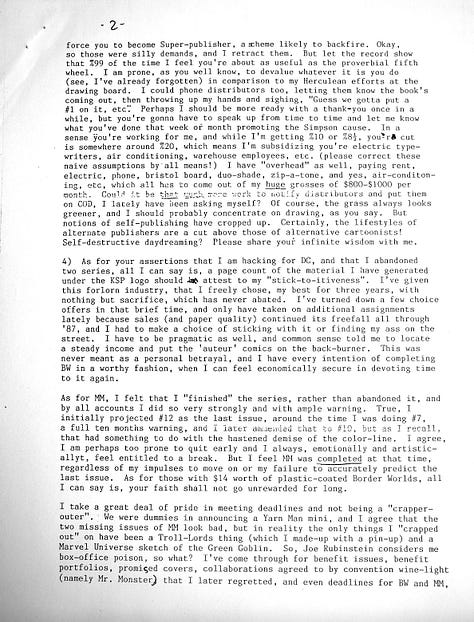

The above page, dated April 2, 1987, is important for several reasons. First, the publisher seems to accept in principle Megaton Man #11 for publication as a black-and-white comic (like Border Worlds)—I certainly read it that way at the time, although they express vague misgivings about the numbering, which I ignored.

Judging from the second paragraph, the publisher had no doubt raised the possibility of a new #1 on the cover with me over the phone, although here they seem to agree with me: “Regarding the honesty of the numbering, price, lack of ruthless gimmicks, etc., I sympathize totally.”

The matter of numbering Megaton Man #11 would seem to have been settled, then.

Unfortunately, this would be one of the last direct communications from my publisher to strike such a collegial and cooperative tone.

There is nothing in my extant files (and no documentation I can ever recall) pertaining to Megaton Man #11 or its numbering between spring and fall of 1987. I was completing Border Worlds—or rather making the very painful decision to place it on hiatus, since sales could no longer cover my cost of living—and had just begun freelancing for the early issues of Wasteland.

Presumably, we touched on the issue of numbering by phone, and I wasn’t happy.

Judging from the above letter from November 18, 1987, the publisher had become more insistent and adamant about renumbering Megaton Man #11. I was incensed by this apparent bait-and-switch, especially after suspending Border Worlds, and deeply resentful of the publisher for holding me over a barrel after I had already made a start on the new material.

No doubt, this anger affected the tone of my missive. But I stand by every single suggestion and argument I make as not only perfectly sensible (and retrospectively proven true), but also made in the best interest of the publisher as well—had they been open to following my advice.

Note: The above letter was date-stamped with annotations and sent back to me along with the nine-page response, below.

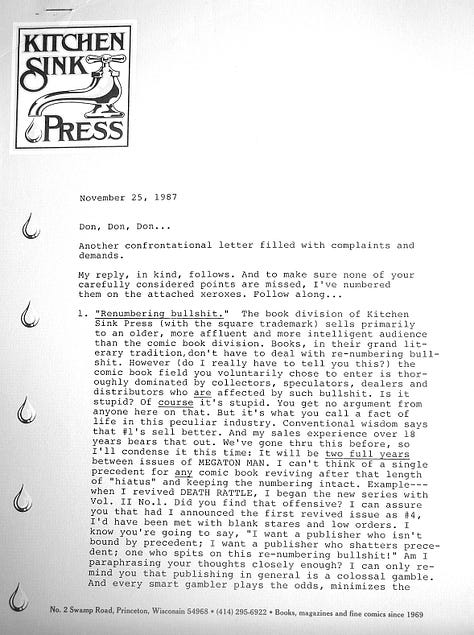

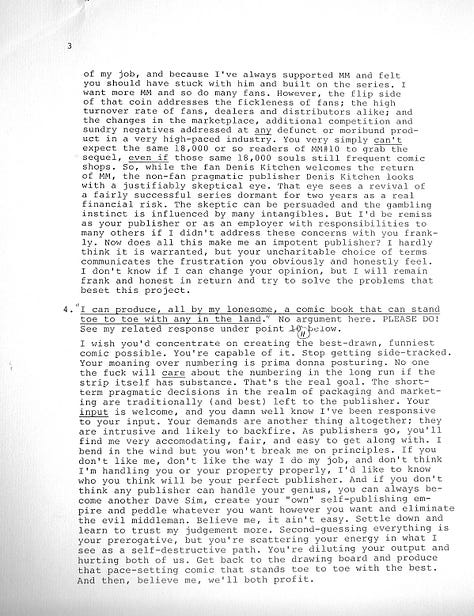

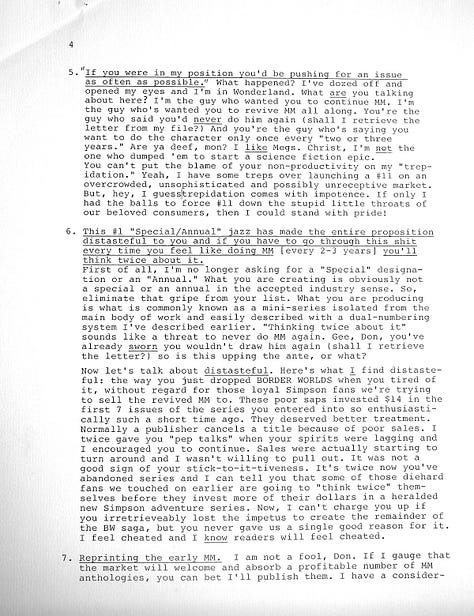

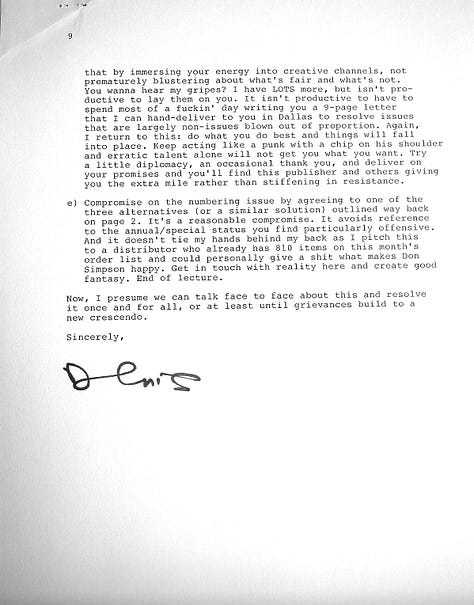

The letter above, dated November 25, 1987, is singularly remarkable for several reasons. First, the publisher claims they are responding “in kind” to my letter, the first of many exaggerations to come. Although my letter had been critical, I’m hard-pressed to find in it the kind of bullying, verbally-abusive name-calling they unleash in response.

Interspersed throughout, they call me a sellout, a hack, a primadonna, a spoiled holdout blackmailer, a jerk, a punk, a “genius,” a traitor who “cheated” both readers and publisher, a quitter, and and an insecure egotist—ten derisive names in all. None of these, in my view, are justified by my previous letter or in any correspondence that has survived in my files.

In fact, I had just completed seventeen bi-monthly issues—ten of Megaton Man and seven of Border Worlds—and had proven myself the most consistently reliable, productive, and profitable cartoonist the company would ever publish.

I’m sure they are studying the above document at the Columbia Business School as an example of how to motivate content creators, and the name-calling and verbal abuse will be further explicated in the forthcoming documentary about the publisher.

Note: The letter of November 25, 1987 (the day before Thanksgiving) appears to have been hand-delivered to me at the Dallas Fantasy Fair. Why the publisher would not have made use of the occasion to sit down with me to discuss our issues over coffee, referring to the letter only as a list of talking points but otherwise keeping it folded up in his coat pocket, is completely inexplicable to me—not to mention foolish and tragic.

Some things can’t be unsaid, and this barrage left permanent damage.

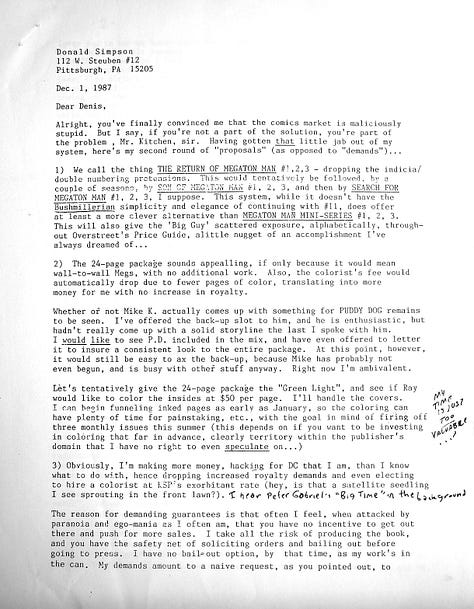

My response, dated December 1, 1987, is a complete and embarrassing capitulation. The arguments I make at the time I have repeated elsewhere and I hold have been largely borne out by subsequent history.

In retrospect, I should have regarded the November 25, 1987 letter as expressing the publisher’s declination to publish Megaton Man #11 and moved on.

Indeed, not long after this letter, I lost all interest in creating more Megaton Man at all. How I continued publishing with Kitchen Sink Press for another three years seems completely insane to me now.

I suppose my desire to prove the publisher’s many unfair assertions wrong overrode common sense—a species of Stockholm Syndrome. But my fondness for the publisher was forever destroyed, and the situation never improved. I finally, inevitably, sadly ended the arrangement in 1990. I’ve never regretted the decision.

My only regret was that I hadn’t done so long before 1988 began.

I elaborate on this in the Afterword to the forthcoming The Complete Megaton Man Universe, Volume I: The 1980s.

A couple of comments to this post have taken me to task, blaming me for triggering the publisher's 9-page retort with my November 18, 1987 letter, suggesting I could have benefited from software to restrain my worst impulses, that I lived on a different planet than my publisher (I can only agree), and so on.

I stand by what I wrote in 1987 and further what I write above; I have already offered my side of the story more thoroughly in the Afterword to the forthcoming THE COMPLETE MEGATON MAN UNIVERSE VOLUME I: THE 1980s, which, barring World War III (which is only apt), should reach our shores by September of this year.

Although I refer to it as "the nine-page letter," my publisher's response contains about eight pages of text, minus the logo letterhead. Of this, six-and-a-half pages will seem reasonably cogent and even offer useful insights into the state of the industry in 1987, but this is misleading. The arguments made and the facts brought to bear are either completely irrelevant or arguably beside the point. The other one-and-a-half pages include exaggerations, willful distortions, and outright lies which I address further in the Afterword, and will happily annotate further if necessary.

For the time being, suffice it to say that the publisher had previously agreed to publish MEGATON MAN #11 as a black and white comic in February 1987; over the course of the year, they unilaterally decided it needed to be color mini-series with a new #1 on the cover. It is telling that not even estimates of numbers are provided--only the hunch that that a new #1 would sell better.

I thought a new #1 would insult the intelligence of my fans--it was a ploy worthy of a shabby outfit like Solson, not an arthouse publisher such as Kitchen Sink Press--and said so at the time. More importantly, I stated that maintaining the numbering was important to me and my sense of continuing an organic narrative. That in itself should have been sufficient. (I cite several instances of comics series interrupted one way or another that maintained numbering before and since, including several at Kitchen Sink Press, in the Afterword.)

Nonetheless, we did things their way. History, I believe, has proven me right; the gimmick did not work in the long run or even the short run. I would even go so far as to argue that a MEGATON MAN #11 through #14 would have stood a better chance of picking up where MEGATON MAN #10 left off--although I'm sure as I make this assertion it will surely only bring on another request for smelling salts from the publisher. I'm also convinced that the occasion of a MEGATON MAN #11 through #14 would have been the perfect time for reprints of MEGATON MAN #1 and #2--not all in the same month, mind you.

It's more than a bit ironic that while the publisher adamantly refused to reprint those immediately-sold-out issues, they still suggested that I just keep redrawing them over and over again in different guises--a narrative stasis that completely contradicted the character-driven direction I was planning and that my editor, Dave Schreiner endorsed.

I will simply note here that after THE RETURN OF MEGATON MAN #1-#3, which I had plotted and began thumbnailing before my publishers withering diatribe of November 25, 1987, I only managed another two-and-one-third more MEGATON MAN comic book issues (the black-and-white one-shots MEGATON MAN MEETS THE UNCATEGORIZABLE X+THEMS #1, YARN MAN #1, and PTERANOMAN#10) before my imagination completely shut down. I simply could not thread the needle--the cognitive dissonance between my editor and publisher was too great.

And, by the way, I don't think Dave Schreiner was every privy to the nine-page letter.

Again, I address this in greater detail in the Afterword.

As for triggering, I am convinced this had more to do with the hardships of 1987, a painful divorce, the pre-holiday blues, and the embarrassment of seeing a "cornerstone author" have to resort to freelance just to keep a roof over his head, rather than any of the sensible suggestions I made at the time. Sometimes marketing considerations conflict with narrative interests--comic books, like other forms of narrative, are not cans of beans.

One can take whatever side one wishes; I'm not going to reply any further on this thread or to anyone who feels they have a more omniscient view of the matter. I simply note for the historical record that the verbal abuse and name-calling heaped upon me at the time was utterly traumatic, completely undeserved, and had long-term consequences.

One of the reasons I look forward to the publication of the COMPLETE collection is that I will no longer have to count the number of Kitchen Sink Press MEGATON MAN comics on my fingers; they will finally be brought together, reconciling a narrative fracture that was never of my making.

As Jeff Lynne sang, "The record isn't all it might have been."

But more importantly, as Mort Sahl used to say: Onward.