I mentioned in a recent post that I was dismayed at the loss of detail on Megaton Man Meets the Uncategorizable X+Thems #1 (Kitchen Sink Press, April 1989) when I saw printed copies.

Jim Kitchen, production manager and younger brother of the publisher, took my concerns seriously and asked the printer (a supplier new to Kitchen Sink Press and perhaps to comics) to reshoot a test page with a negative and a blueline.

Jim wrote to me:

Dear Don,

I went to the printers and raised hell about the loss of detail in Megaton Man. They were embarrassed and apologetic. They swear they will not let the camera room slip up again. The camera room reshot the first page negative, which I include with you original, and the detail is much better. I had them make another blueline, also enclosed, and I hope that this meets with your standards. Let me know what you think.

They also are checking on better paper. I’ll keep you posted.

Regards,

Jim (I eat printers for breakfast) Kitchen

This is noteworthy for several reasons. First, while my relations with elder brother

Denis had completely soured after 1987 and improved nary a whit in my remaining three years at the publisher, I remained on fond terms with other employees at Kitchen Sink Press, including Jim. And the company as a whole, to their credit, remained conscientious regarding production standards. Jim certainly aimed to please.

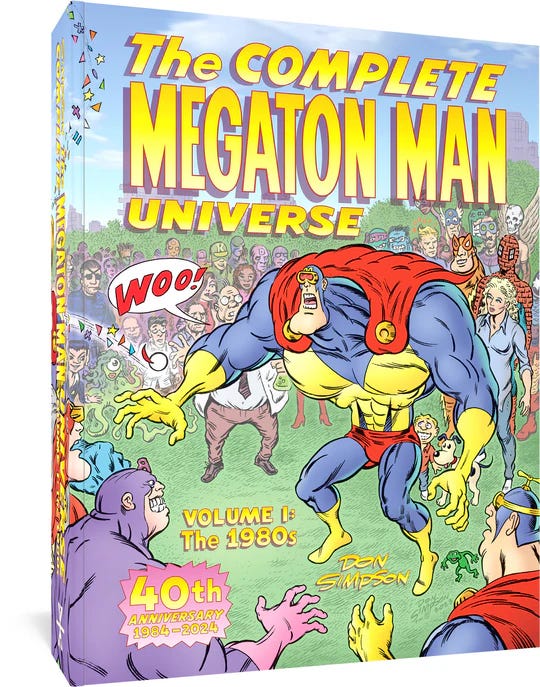

It’s also interesting that Jim doesn’t refer to Megaton Man Meets the Uncategorizable X+Thems #1, but rather to “Megaton Man”—apparently, he never got the memo that I had wantonly killed the series with issue #10 and was condemned to only #1s by this time, which would have been the fourteenth Megaton Man comic book.

He closed his note with “I eat printers for breakfast”—a reference to a pinback button where Megaton Man shakes his fist and says, “Are you kidding? I eat X-Men for breakfast!”

Jim would subsequently contribute a compendium of bad puns for the inside front cover of the next Megaton Man comic book: Yarn Man #1.

I never knew how much anyone at Kitchen Sink Press was aware of the discord between me and Denis or privy to the caustic communications that had needlessly unfolded between us. I’m not sure it would have made any material difference.

This was just another tragic aspect of an unfortunate situation I felt trapped in until 1990, when I could no longer take it anymore and broke ties with the publisher.