As explained in the three previous posts, I penciled and lettered the first twenty-two pages of Bizarre Heroes #1 (Kitchen Sink Press, May 1990)—with inked pages 1 through 6 and a pitch cover—and made several stapled photocopy sets to show to fans, fellow professionals, and prospective publishers.

They are the only surviving documentation I have of the penciled and lettered state for pages 7 through 22.

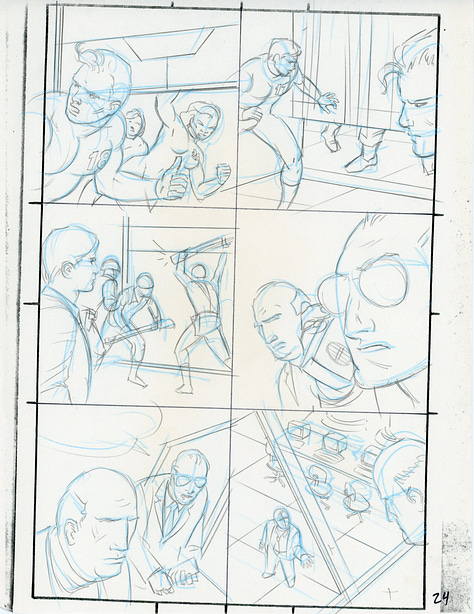

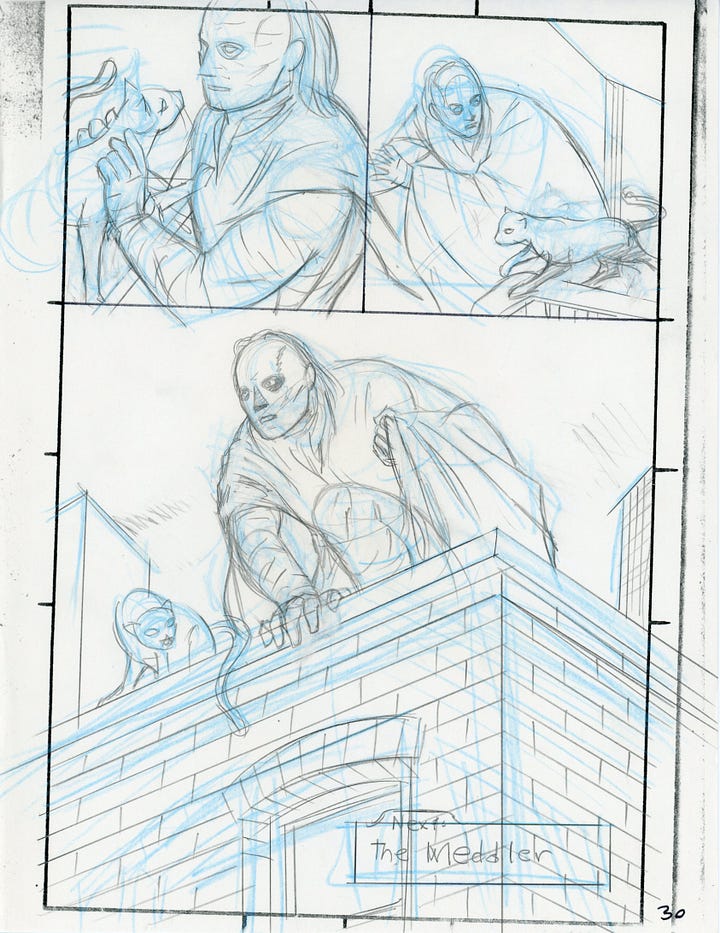

After acceptance by Kitchen Sink Press, I proceeded to complete the remaining pages. Whereas before I had used 5.5” x 8.5” rough thumbnails for pages 1-22, posted previously, I switched to the larger 8.5” by 11” size for the remaining pages 23 through 30, shown here.

I did not make copies of these pages at the pencil and letter stage, apparently, but the final black-and-white art can be seen online and will be included in volume II of The Complete Megaton Man Universe from Fantagraphics, now in the design stages.

As I discussed previously, acceptance by Kitchen Sink Press for this book—unrelated at the time to either Border Worlds or Megaton Man properties—was not a given and something of a surprise. I was toying with the idea of self-publishing the title, since it would not have fallen under Kitchen Sink Press’s “first right of refusal” clause written into my previous contracts. As a new IP, I was free to pitch it to other publishers but hadn’t gotten very far by the time editor Dave Schreiner (I assume) showed interest.

Sorry, but the extant correspondence I have in my possession is incomplete on this point, and I’m guessing a lot of this was discussed by phone. I know there was never a contract written up or signed for Bizarre Heroes, so in theory I was not bound to Kitchen Sink Press even for any sequel issues.

[Text continues below.]

On self-publishing, it needs to be pointed out that in the late 1980s, outside of Dave Sim and Cerebus and Richard and Wendy Pini and ElfQuest, there were precious few successful self-publishing models to follow. This would change in the next decade, with Jeff Smith and Bone and several others—I will discuss the self-publishing movement and my involvement in future posts—but for the time being, I felt trapped.

I should add here that “self” here is somewhat deceptive—Deni Loubert was instrumental in the success of Cerebus, just as Vijaya Iyer was to Bone—one could fairly describe Cerebus, ElfQuest, and Bone as examples of husband-and-wife publishing without any disrespect, as it so happens. But more on that another time.

It is interesting to note that in my extant correspondence with my erstwhile publisher, the possibility of self-publishing is held out as a possibility a couple of times—but not unconditionally. To quote the November 25, 1987 letter posted previously concerning Megaton Man #11:

If you don’t like me, don’t like the way I do my job, and don’t think I’m handling you or your property properly, I’d like to know who you think will be your perfect publisher. And if you don’t think any publisher can handle your genius, you can always become another Dave Sim, create your “own” self-publishing empire and peddle whatever you want however you want and eliminate the evil middleman.

In addition to being a shamefully childish taunt and a needless putdown—“genius” with implied scare quotes is completely uncalled for, and only one of at least nine instances of name-calling and bullying verbal abuse in the nine-page letter—the publisher is also careful not to suggest I find another publisher. The choice is either to self-publish like Dave Sim or remain enslaved to Steve Krupp—the publisher’s more than apt alter-ego.

If you don’t like how I’m handling you or your property properly, then why don’t you find another … I mean, I’d like to know who you think would be your perfect publisher.

And, as Steve well knew, I was unlikely to gather the resources necessary to self-publish with the poverty-wages from an arthouse publisher and beginner page rates as a freelancer. Therefore, it was a cruel taunt as well.

Or give self-publishing a try—when I know for a fact you can’t even afford rent or beans on what you make from me.

Any mature, sensible person would have composed a half-page note—saving eight-and-a-half pages of one-finger typing—more along the lines of:

As for Megaton Man #11, sorry, no can do. My gut instinct is, without a #1 on the cover—even in black-and-white—it’s just too risky. Best of luck continuing Megaton Man elsewhere.

In my most cynical moments, I wonder whether the publisher’s mania for #1s and the onslaught of the nine-page letter wasn’t simply about destroying my self-confidence and rendering me useless a freelancer or creator for other publishers—a scorched earth, war of attrition mentality.

When I had proposed Megaton Man #11, I had just created seven issues of Border Worlds, a multi-issue storyline. While this had emphatically failed in the marketplace, it was a more than worthwhile learning experience because I was now thinking of Megaton Man in longer story arcs—planning at least #11 through #14 and even soliciting feedback from my editor.

With the imposition of the publisher’s #1 edict—as I had predicted—such long-term plotting and planning was shattered, and by 1989 I was reduced to cobbling together whatever material I could for yet another #1 for the publisher. Pteranoman #1 would be my final attempt in this regard.

This wasn’t just imperfect publishing—it was incredibly stupid, foolish, short-sighted, counter-productive, cutting-off-your-nose-to-spite-your-face publishing.

Evil? You said it, not me.