Whenever something new emerges on the scene, it takes a while before fan appreciation turns into professional competence. Let me try to explain what I mean.

For example, when Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, and Steve Ditko laid the foundations for the Marvel Comics Group, there were lots of other competent artists around, but few who could do more than ape the dynamism and mystique of Kirby and Ditko.

Don Heck, George Tuska, and Gene Colan all did a valiant job—and fans love them for it—and early Marvel is unthinkable without them. But it wasn’t until Jim Starlin—who practically was taught to draw by Kirby and Ditko, and who perfectly fused their styles together—and later Rich Buckler and Ron Frenz, who fused Kirby and Ditko with Buscema (and Romita, in Ron’s case)—that the influence of early Marvel began to bear fruit, and a How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way house style was well and truly born.

The same could be said for the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird, influenced by Frank Miller, created something new—and soon brought on artists like Rick Veitch, Mark Martin, Richard Corben, and many, many more—to do their take on the Turtles at Mirage and subsequently at Archie, to meet overwhelming demand from fans. Some were better adapted to the task than others.

I was but one of many asked to undertake TMNT assignments. I was neither the most prolific nor the best-suited for the task—let’s not kid ourselves—but I was grateful for the work and tried to do my best. I had not grown up with the Turtles and couldn’t be described as a “fan”—I was just a pro trying to do a thorough job.

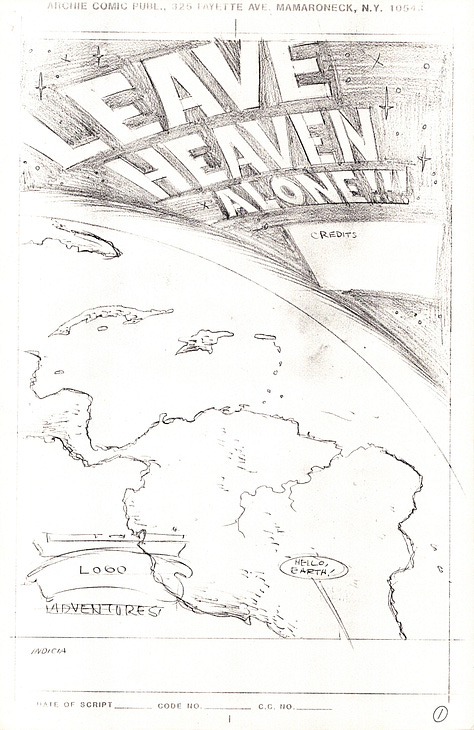

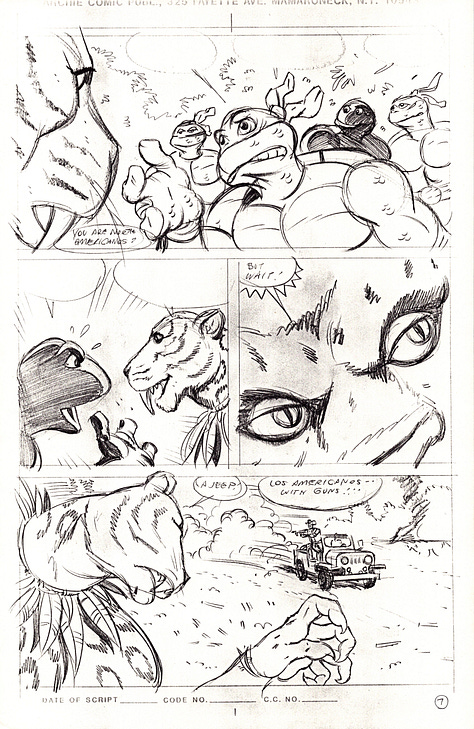

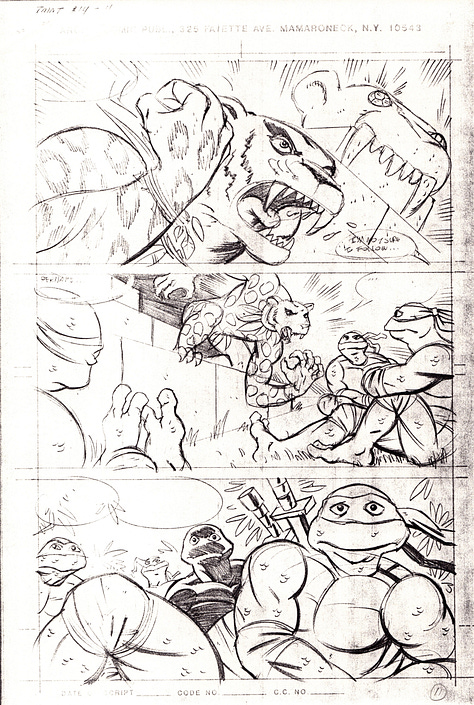

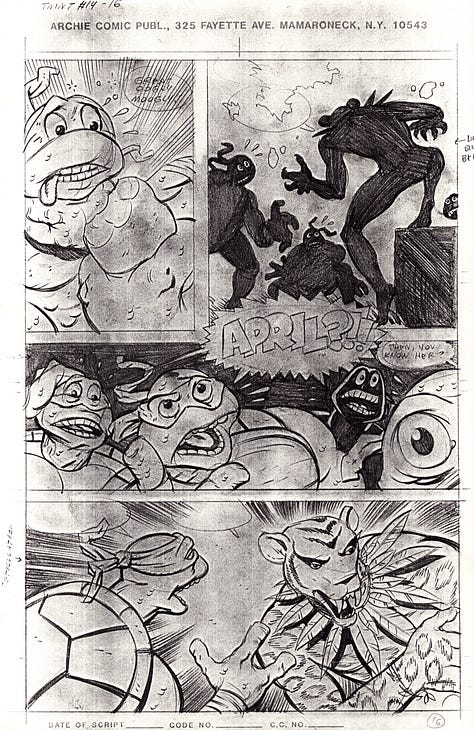

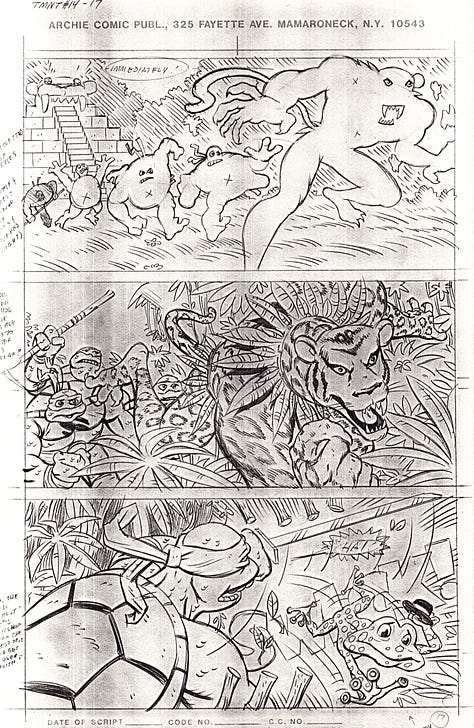

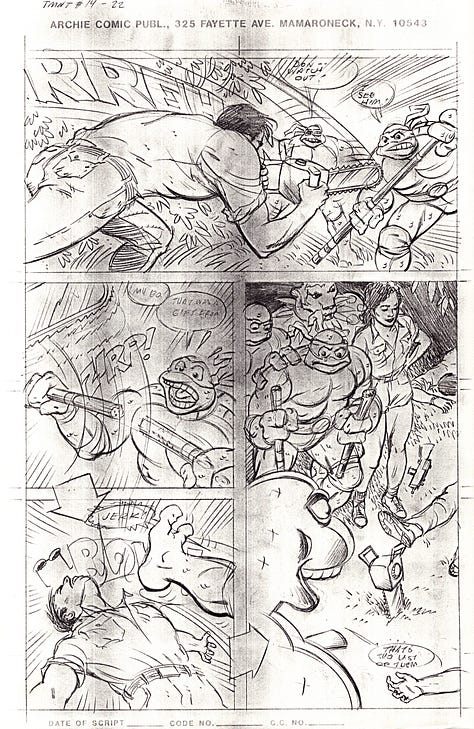

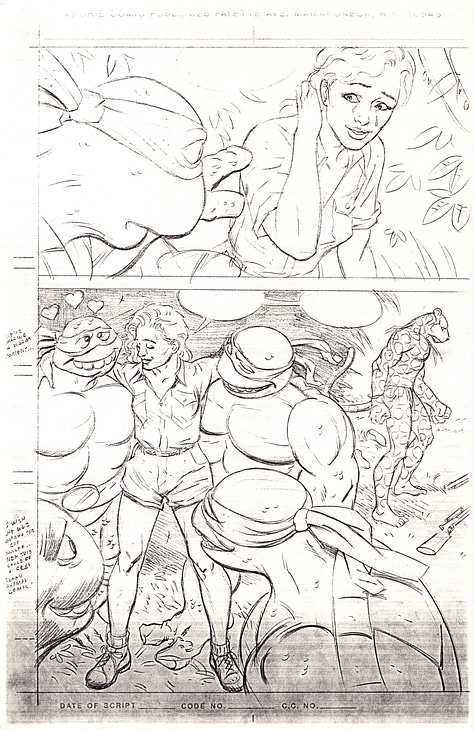

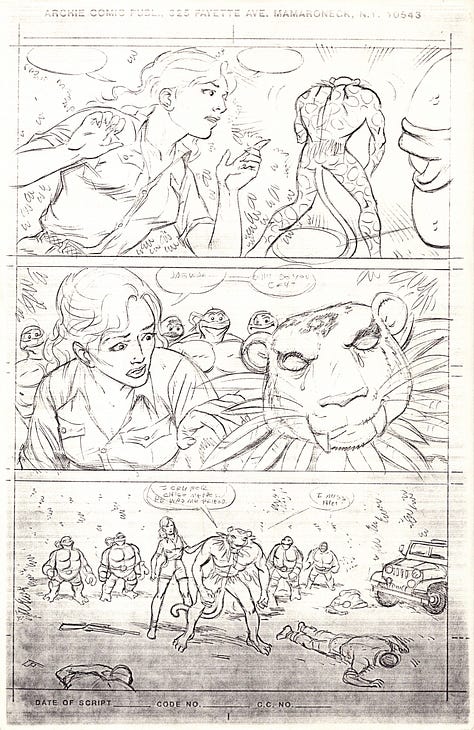

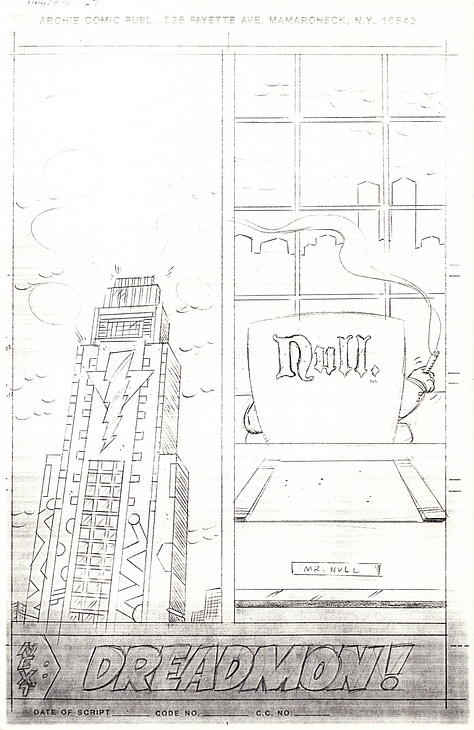

I drew a couple things released by Mirage, then a few more released through Archie. In those days, Mirage Studios handled everything, keeping at least some measure of control over quality and consistency. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Adventures #14 was my first assignment for Archie, if I’m remembering correctly. The Archie Turtles was based on the animated cartoon show rather directly on Eastman and Laird’s comic.

It turned out to be one of the few freelance jobs where I only penciled—usually, I also lettered and inked a job from a supplied script—editors liked the one-stop shopping I provided. I also inked a couple other Turtles Adventures and finally penciled, inked, and lettered at least one more.

I guess you could say I’m an old Turtle artist from way back; I can’t deny it. But I was never more than an outlier.

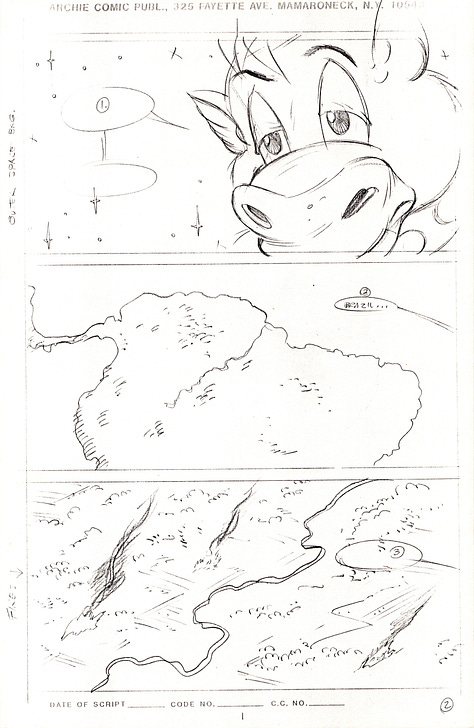

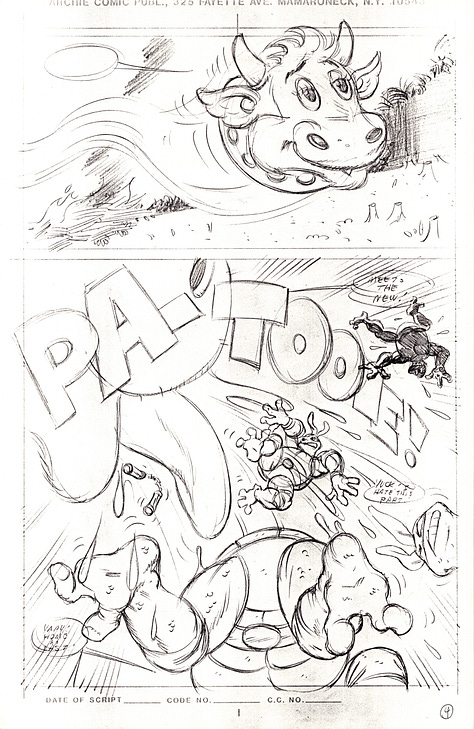

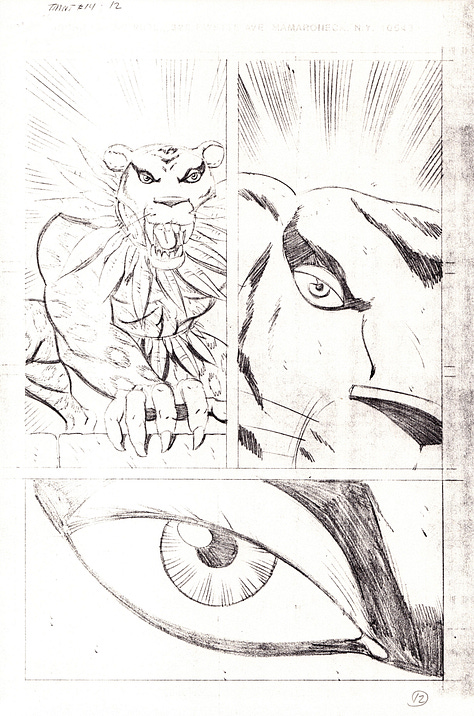

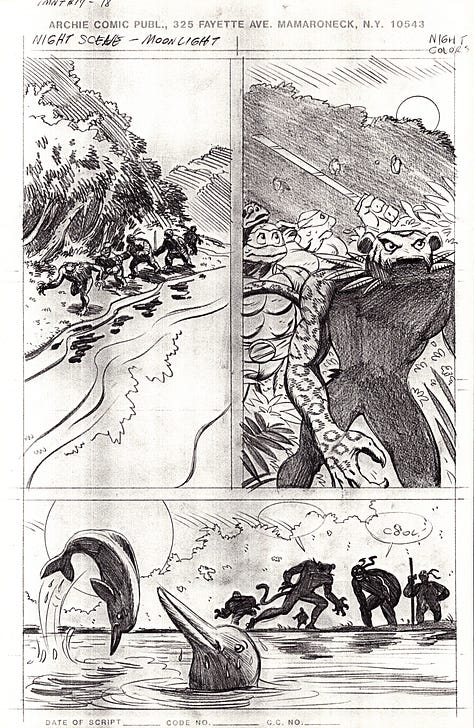

These scans are made from a really inferior set of photocopies in my files. The credits include: Dean Clarrain (Stephen Murphy), writer; Dan Berger, inker; Gary Fields, letterer; and Barry Grossman, colorist. I think I worked from a full script.

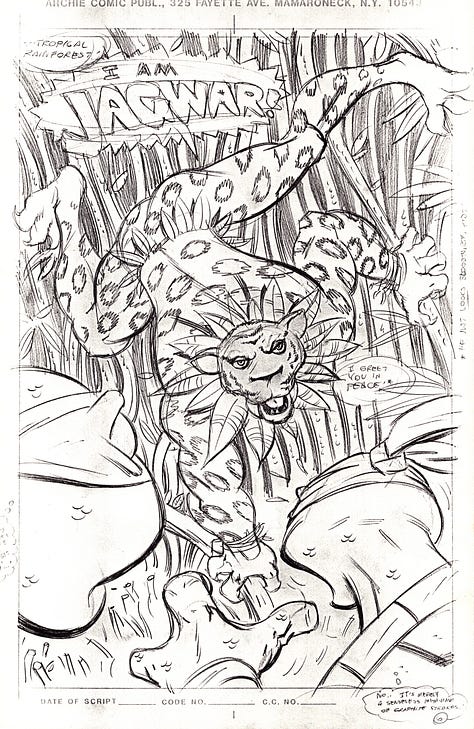

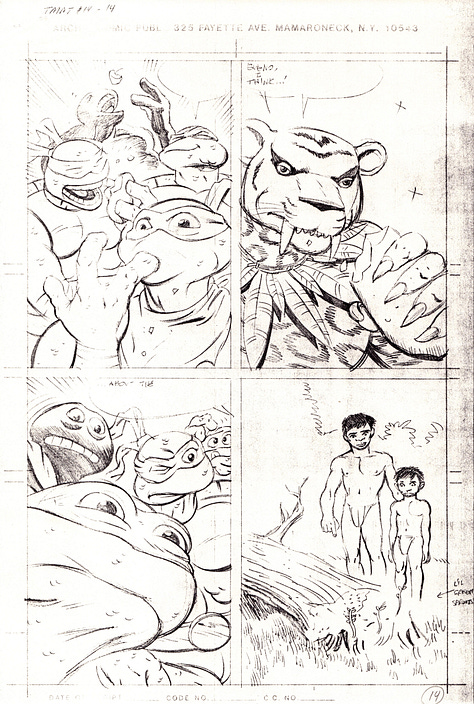

The story, paradoxically, emphasized drama rather than humor. I tried to bring a Kirby-Marvel feel to it, and I think I managed a few nice touches. I would like to have inked and lettered this job myself; I particularly liked drawing Jagwar. Don’t ask me why April’s hair goes from black to lighter outlines, but I was learning on the job.

Stephen Murphy’s (Puma Blues) use of a pen name may hint at how the Archie Turtles were regarded at the time. As licensed funny animals, I got the sense that it was considered the lowest of the low among freelancers, and I always felt the series at times was unnecessarily rushed and shoddy—as if it couldn’t be good. I thought certain freelancers should have brought more to it—Kirby never snoozed on the job simply because it wasn’t perceived as the most prestigious assignment in the world.

Although my “take” on the Turtles never received much love at the time—and my “rubber-suit look” deserved even less—I have since met a number of fans at shows for whom this was one of the first comics they ever read, if not their very first. They retain a certain fondness for it that only a fan can have for an early comics reading experience—and I’ll take the compliment.

I’d like to think I could do the job better now—I feel that way about all my work from the twentieth century, whether freelance or creator-owned. Certainly, it would be easier to reference Jeeps and jungle flora and fauna on the internet now, and my indigenous peoples, Aztec monuments, and Mexican characters could have been a lot more authentic—and less stereotypical.

But I tried my best—I gave it the old college try!

What’s even more remarkable to me now is that in those days, even if your creator-owned work foundered, as mine did—Megaton Man and Border Worlds by 1989 for various reasons were completely lost in the Direct Sales marketplace—one could still find ample freelance work to pay the bills and even learn the craft on the job. Such opportunities simply don’t exist today in quite the same way.

I realize in retrospect that I learned a great deal from freelancing and value these experiences far more now than I did at the time. Had I focused on penciling or inking instead of trying to do it all, I may have developed faster as a cartoonist. Who knows?