I’ve posted previously on the years 1984 and 1985, as covered by Kitchen Sink Press, the First 25 Years by Dave Schreiner. The entire text of this book can be found at Archive.org and is well worth the read. Thanks to James Banderas-Smith for pointing it out to me.

From 1984 to 1990, I published some twenty-five comic book issues and one book collection. These included some sixteen issues of Megaton Man comics, eight of Border Worlds, and what I consider the “pilot episode” of Bizarre Heroes. Megaton Man, Volume I, an oversized hardcover and trade paperback, collected the first four issues, and a second printing of the immediately sold out Megaton Man #1 appeared in 1989, too late to help build a readership, in my view.

While I’ve remarked on the happier, early years of my six with the company, as reflected in Dave’s history, the later years—1988 to 1990—I have not remarked on, possibly because I skimmed over them at the time when I got my copy of the book.

I should back up to say that Dave Scheiner was the editor of Kitchen Sink Press, and a minority owner; he was one of only four full-time employees at the company that included Denis Kitchen, publisher; his wife Holly Brooks, office manager; and Pete Poplaski, art director. Brother Bill Poplaski and Ray Fehrenbach also worked freelance as colorists, and various others, including brother Jim Kitchen, worked in the warehouse from time to time.

When the book appeared in 1994, Kitchen had just moved operations from rural Wisconsin, were I had lived for just over a year in 1985 and 1986, and taken over Tundra Publishing, the company started by Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles co-creator Kevin Eastman, located in Massachusetts.

By this time, 1994, I was no longer affiliated with the imprint; thanks to a pile of money earned through Image Comics, I began self-publishing Bizarre Heroes through my own imprint, Fiasco Comics Inc.

Dave, I understand, had stayed behind in Wisconsin—Madison, to be exact, where he spent his weekends while editor—with his wife, Leslie Luttrell, and I presume his health insurance. Dave would eventually die from the Crone’s Disease that was a chronic condition he had battled for some years.

I’m not sure what Dave’s financial relationship with Kitchen Sink Press continued to be after the move—whether he took a buyout or what—but in any case, his history of the company was likely his last significant project for Kitchen Sink Press.

I’ve previously noted that the few typewritten notes from Dave are highly precious to me, since they offer encouragement for the character-driven direction I planned to take Megaton Man with issue #11, after a seven-issue interregnum for Border Worlds—away from IPs initial parody impetus. This advice was diametrically the opposite of that given by Denis, who wanted only more repetitious superhero parody that attacked “worthy targets”—the bigger competition—and couldn’t have cared less for what he regarded as my “convoluted storylines” exploring the personal lives of the characters.

What strikes me about the few mentions me and my work recieve in the history after 1987—and about the book in general—is how cursory the remarks seem. Although the text is copyrighted by Dave, he was clearly writing about his former partner, and needless to say, the book was being published by new Tundra-fueled Kitchen Sink Press.

What is striking to me is that, while Dave’s overview of the earlier years at the company seem to be more concerned with the social impact their comics hoped to have on society as well as storylines and characters, Dave’s mentions of cartoonists, titles, and projects in the late 1980s and thereafter are reduced to cursory remarks on whether a book or comic “did well” or poorly, or “sold well” or poorly.

This seems a bit sad to me.

In regard to my own work, while mentions of it in 1984 through 1986 are relatively upbeat and fulsome (Megaton Man made “the biggest splash” of 1984 and I was the “cornerstone author” of 1985), the mentions after that are cursory and downbeat, and there are a few inaccuracies and omissions I never bothered to flag in 1994.

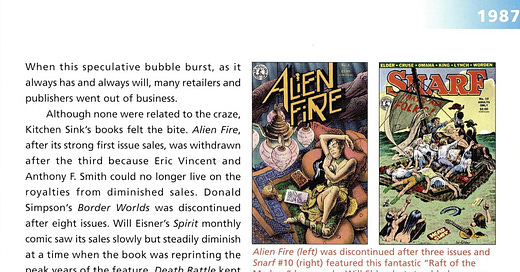

In 1987, Dave notes on page 81, “Donald Simpson’s Border Worlds was discontinued after eight issues.” Dave must have been relying on his memory here; in fact, there were seven issues of Border Worlds. An eight issue, Border Worlds: Marooned #1, appeared in 1990, essentially as a one-shot follow-up.

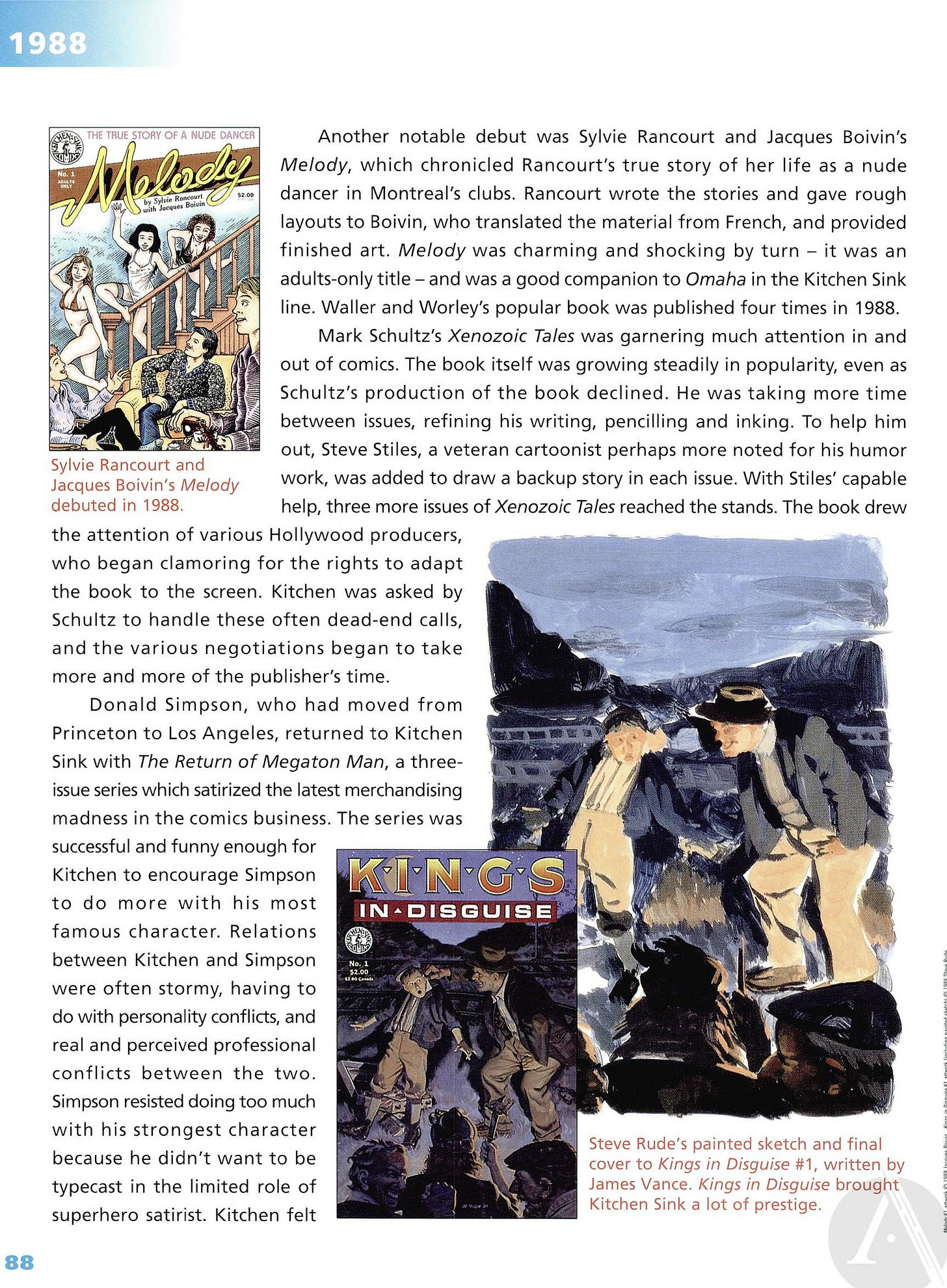

For the section on 1988 (pages 88 and 89), Dave notes,

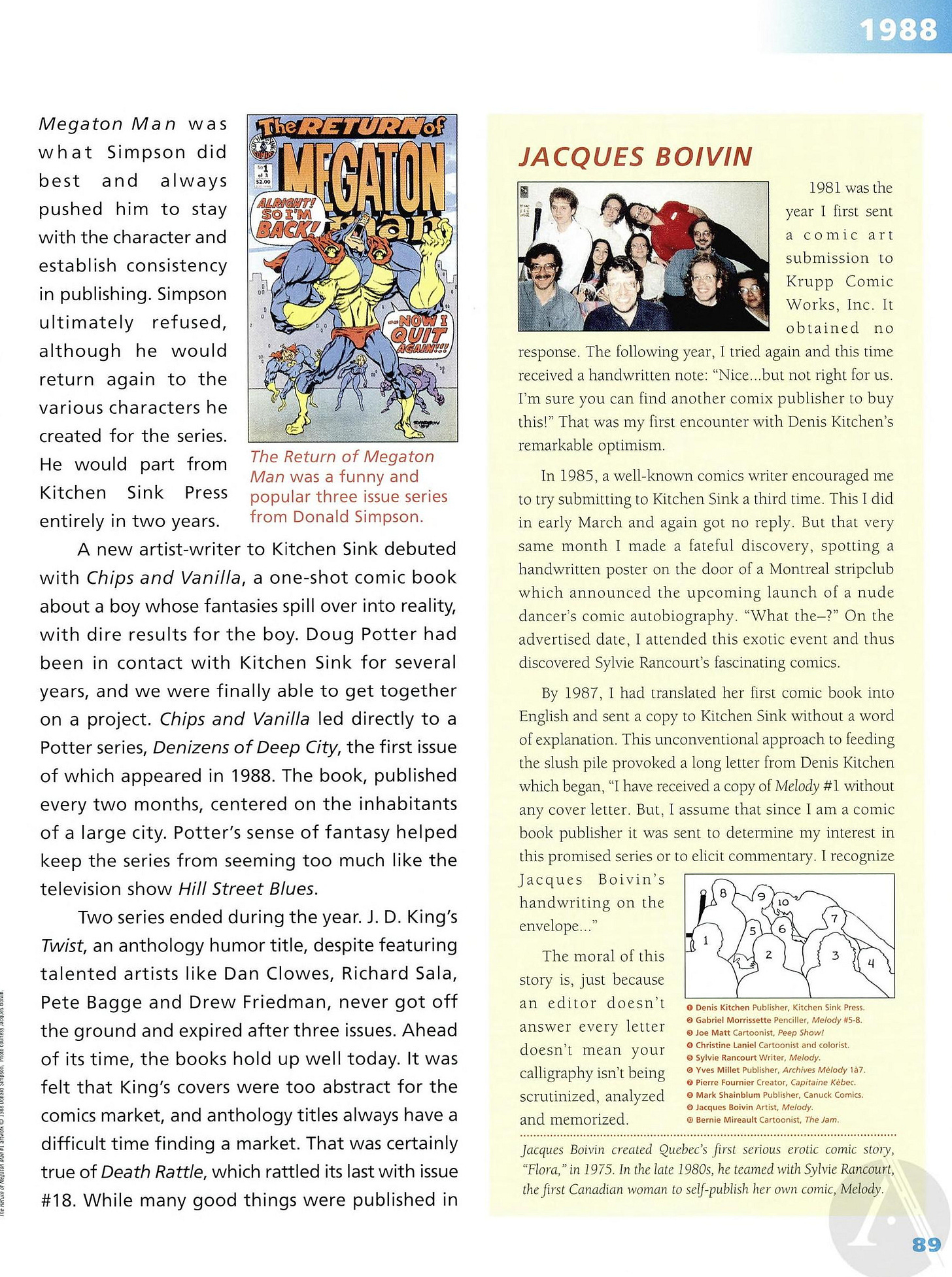

Donald Simpson, who had moved from Princeton [Wisconsin] to Los Angeles, returned to Kitchen Sink with The Return of Megaton Man, a three-issue series which satirized the latest merchandising madness in the comics business. The series was successful and funny enough for Kitchen to encourage Simpson to do more with his most famous character. Relations between Kitchen and Simpson were often stormy, having to do with personality conflicts, and real and perceived professional conflicts between the two.

Simpson resisted doing too much with his strongest character because he didn’t want to be typecast in the limited role of superhero satirist. Kitchen felt Megaton Man was what Simpson did best and always pushed him to stay with the character and establish consistency in publishing. Simpson ultimately refused, although he would return again to the various characters he created for the series. He would part from Kitchen Sink Press entirely in two years.

This requires some unpacking. First, I moved to Van Nuys, California, in the San Fernando Valley north of Los Angeles, in the summer of 1986; by November, I moved to Pittsburgh, where I conceived Megaton Man #11—what became The Return of Megaton Man #1-#3.

Being away from Kitchen Sink Press, I never discussed with Dave the unfolding acrimony between me and Denis; I felt running to mommy, as it were, would only invite further humiliation and verbal abuse from Denis. In any case, to this day I will never know Dave’s thoughts on the matter, or how much he was privy to the communication between me and Denis.

It seems in this passage that Dave is more or less hewing to the company line—that Denis always encouraged more Megaton Man from me, and that the “stormy” relations and “personality conflicts, and real and perceived professional conflicts between the two” were taken verbatim from Denis, and is a drastic oversimplification at best.

I have expressed elsewhere that Megaton Man #11 represented not only a second wind and firmer foundation for the series going forward, but for all intents and purposes a complete reinvention of the series—moving the characters and action from Megatropolis to a Midwest college campus, and concentrating on a character-driven exploration of the personal, civilian lives (secret identities) of the megaheroes set in a counter-culture milieu that would have held even more appeal for Kitchen Sink Press’ core audience.

I have further maintained that any fool could have seen that I was only an encouraging nudge from returning to Megaton Man full-time—or as full a time as I could muster, given that I was forced to turn to work-for-hire freelance in order to keep a roof over my head.

When the publisher insisted on a new #1, I strenuously objected, warning that this was a feckless ploy that would insult my readers’ intelligence, present me with needlessly complicating narrative obstacles—having to justify a new #1 with each new installment of Megaton Man—and not produce higher sales or enlarge the readership in the long run.

In retrospect, I believe the withering reply that came from the publisher had less to do with numbering but simply with who was the boss, and was triggered more by Denis’s recent divorce from Holly and the fact that his “cornerstone author” of recent years had to resort to freelancing for DC Comics—at beginner page rates that were five or six times what my creator-owned IP had earned.

While it is true that I “didn’t want to be typecast in the limited role of superhero satirist,” it is completely false that I “resisted doing too much with [my] strongest character.” I had devised the four-page plot outline for Megaton Man #11 not because it was requested of me, but of my own volition, and had submitted it to the company in January 1987.

It represented my most fleshed-out story arc for the character to date, and protended a multitude of story possibilities to come.

That Denis “always pushed [me] to stay with the character and establish consistency in publishing” is complete malarkey—so much so that I wonder whether Denis himself did not insert the above passage in its entirety.

As I’ve posted previously, Denis urged that the cast and the storylines I had planned for Megaton Man—a direction Dave had applauded—be subordinated to one-shot spoofs of passing fads like the Dolph Lundgren Punisher movie, an ad-hoc branding strategy that was not only short-sighted and foolish, but as I warned at the time, guaranteed to confuse and confound my creative imagination.

In any case, it was not creator-owned comics by any definition I can recognize. In retrospect, it would have been far better had Kitchen Sink Press had acquired the Cracked brand and set a team of hack creators to spoof “some worthy targets” to his heart’s content.

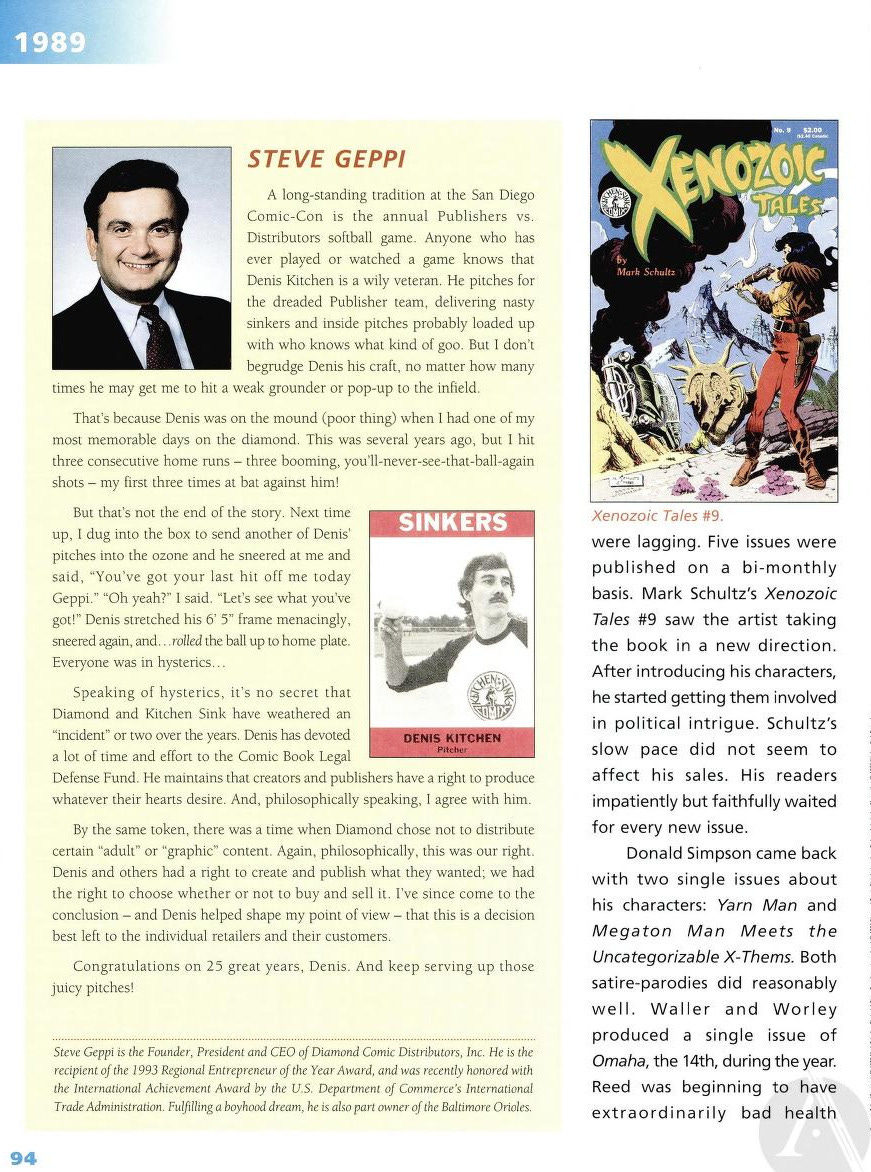

Later, on page 94, Dave’s only mention of my work during 1989 was that Megaton Man Meets the Uncategorizable X+Thems #1 and Yarn Man #1 “did reasonably well.”

Finally, for the chapter on 1990, Dave writes—although I wouldn’t be surprised if Denis had also amended the text here—

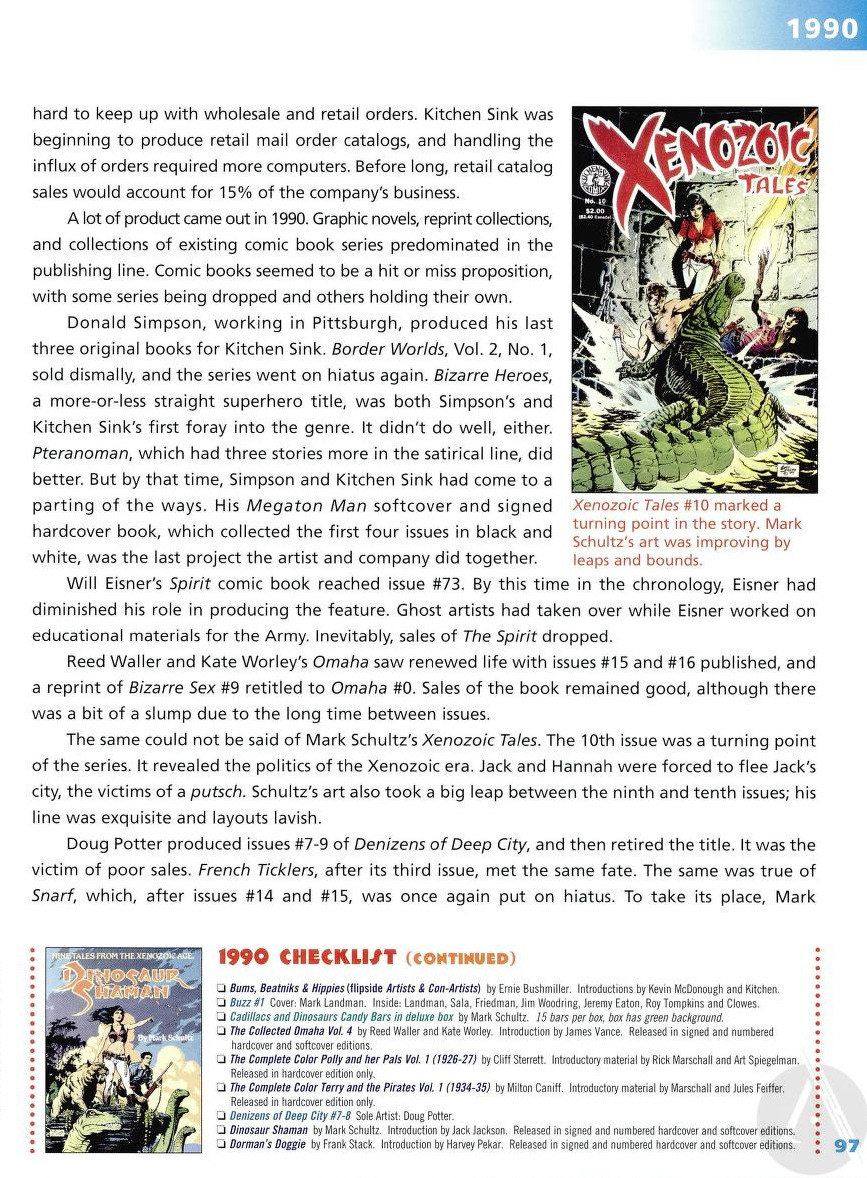

Donald Simpson, working in Pittsburgh, produced his last three original books for Kitchen Sink. Border Worlds, Vol. 2, No. 1, sold dismally, and the series went on hiatus again. Bizarre Heroes, a more-or-less straight superhero title, was both Simpson’s and Kitchen Sink’s first foray into the genre. It didn’t do well, either. Pteranoman, which had three stories more in the satirical line, did better. But by that time, Simpson and Kitchen Sink had come to a parting of the ways. His Megaton Man softcover, which collected the first four issues in black and white, was the last project the artist and company did together.

Again, the remarks that various comics “sold dismally,” “didn’t do well,” or “did better,” sadly, only mark the debased values of Kitchen Sink Press at the time, which had declined drastically from a socially-conscious imprint—the Ben & Jerry’s of comics—to sheer materialism and bottom-line thinking. It is significant that the only thing the history thought worthy to note about Bizarre Heroes was that it was a dreaded straight superhero comic—not a parody—just about the only genre the eclectic but otherwise aesthetically pure Kitchen Sink Press had never “forayed” into.

It also needs to be pointed out that I never held any hopes of Border Worlds: Marooned #1 relauching the series; by this time, I was simply clearing out my inventory. As far as I was concerned, Kitchen Sink Press had ceased being a partner in publishing or IP brand management and was simply an outlet for leftover dreams to see print.

In any case, the idea that I held hopes of returning to Border Worlds full-time—and therefore, that disappointing sales forced the series to go “on hiatus” again—is completely ludicrous.

Also, the Megaton Man collection (which appeared in both softcover and hardcover in January 1990), was not my last project at the company—that honor went to Pteranoman #1, which appeared in August 1990.

In conclusion, it’s no surprise that Kitchen Sink Press: The First 25 Years does not include a passage along the lines of

For six years, Don Simpson was the most dependable, consistently profitable, loyal, and productive cartoonist Kitchen Sink Press ever published—and boy, did we ever screw up a Golden Opportunity the likes of which we would never see again!

But that is more or less the history I would write.

I appreciate your continuing narratives about this era, Don, and I also value the way you set the record straight, again and again. Histories need to be doublechecked, verified, authenticated. That goes for all histories, big or small! It's necessary and needed, whether we are looking at the way the Trump administration removed documentation about Jackie Robinson and Harriet Tubman, or the obfuscations related to comic book publishing.

In thinking about the way your work supported the general output of Kitchen Sink Press, I'm reminded that something similar happened with Fantagraphics. Please note this is hearsay, or me trying to remember something without concrete documentation at hand! But I seem to remember that Fanta was on the verge of going under when their operation was saved by the Eros imprint. You know, the same imprint that published Anton Drek!

Hmmm... Kitchen Sink Press, Fantagraphics... what publisher are you going to save next?